Orbán, Le Pen: will the two leading Russophiles ultimately wreck the ”Pan-European alliance of populist rebels”?

Not long ago, Marine Le Pen’s presidential campaign was reported to have received financial support from Russian funds, a role that is now taken over by Hungary: the French National Rally is about to receive a loan of nearly 10.6 million euros from a Hungarian bank whose name remains undisclosed. Le Pen’s campaign rally on Saturday was greeted by Orbán in a recorded video message, and the two politicians generally share common views on Russia. Views that are nonetheless debated by others. Tolerating Moscow’s politics is not a welcome approach for a number of potential partners, and this might be a reason why a fortnight ago, at a summit in Madrid, right-wing parties failed to establish a European-level alliance positioned to the right from the European People’s Party. Analysis.

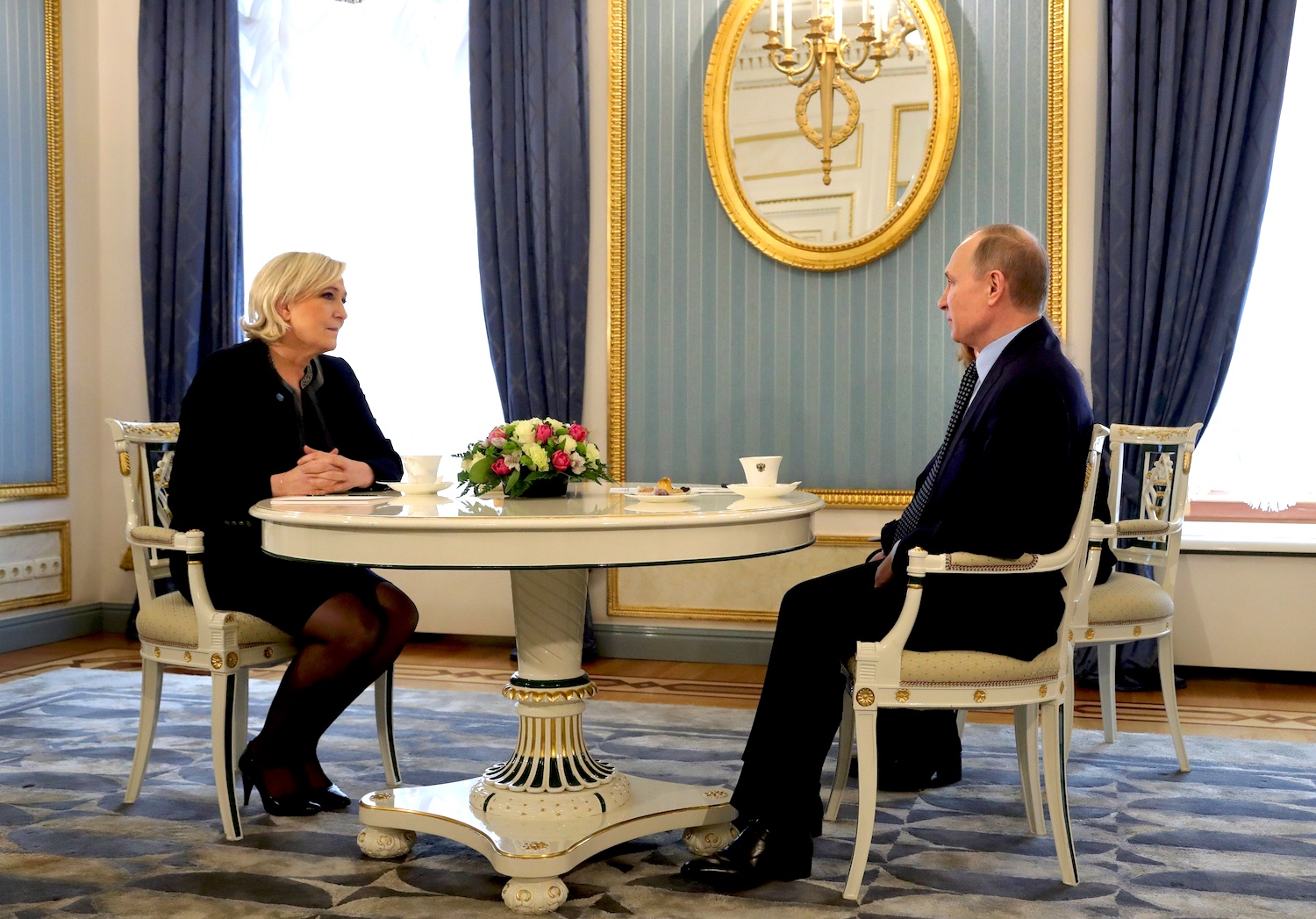

At the end of January they befriendingly pat each other’s shoulders, then a few days later they represent completely opposing views – any guesses what that might be? The answer to this political riddle is: the Polish-Hungarian camaraderie. On January 29, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his Polish counterpart, Mateusz Morawiecki, were pictured as joining hands at the Madrid conference of conservative and radical right-wing parties. The following Tuesday then, one travels from Warsaw to Kyiv, the other from Budapest to Moscow. Mr. Morawiecki vowed to equip Ukraine with ammunition, drones and humanitarian support in response to a growing threat of Russian military invasion, and also to sign a defence agreement with Poland’s eastern neighbour and with Great Britain. Meanwhile, his Hungarian counterpart held negotiations in Moscow with Vladimir Putin on the issue of energy supplies and the infrastructural development of a railway line surrounding Budapest. Later on, towards the end of a joint press conference, Mr. Orbán was made to endure the Russian president’s ten-minute tirade denouncing NATO and listing the names of Central European countries which mistakenly joined the military alliance after 1997. (As a reminder: Hungary joined NATO in 1999, following a national referendum.)

In fact, the Hungarian and the Polish governments tend to have a common stance in numerous political topics (for example, their objection to linking EU funds to the rule of law).

Still, the Polish governing party, PiS, and the Hungarian governing party, Fidesz, have a fundamentally divergent standpoint on the issue of Russia. This is a stark indication of how complicated it is to unite right-wing parties under the umbrella of a European-level alliance which is positioned to the right from the European People’s Party. In fact, the preparation of such an alliance was actually underway in Madrid last weekend.

Despite acting as ideological buddies, these parties have nevertheless differing views on some fundamental issues, hence it should be no surprise that the ”Pan-European alliance of populist rebels” still remains non-existent. Instead of a glorious European revolution, the mountains gave birth only to a mere political coordination office – after being in labour for months. Take it as the sole outcome of the Madrid summit. The story had a different onset, though. It was almost a year ago that Fidesz left the European People’s Party, and Hungarian governmental mouthpieces were almost rejoicing over this development. As argued, the Hungarian governing party would now have a chance to be allied to full-blooded fighters instead of lukewarmish centre-right politicians, thus extending – and not limiting – its room for manoeuvre.

From our own part, Válasz Online was more cautious. In the first place, we noted why Fidesz would have no following among other parties (as some people envisaged mass defections from the European People’s Party). Beyond that, we also showed why it is nearly impossible to bring together in one platform the pro-autonomy Flemish Interest party from Belgium and the Spanish Vox party whose identity is partly based on the fight against separatist Catalans. Or the Polish PiS, the party dreading the Russians and detesting the German extreme right for historical reasons, and the National Rally headed by Marine Le Pen, who showed a brilliant sense for diplomacy in Warsaw where she labelled Ukraine as part of the Russian sphere of interest, or the similarly pro-Russian German party AfD. In addition, a Hungarian example could also be mentioned. For anyone who tends to cherish the idea of a culturally united Hungarian nation the company of AfD and Le Pen would be at least discomforting, as both voted against the Minority Safe Pack Initiative, a European scheme supporting minority Hungarians outside the motherland.

That said, we have not yet brought up the fight of egos: some of the potential allies are more than hostile to one another.

Matteo Salvini, currently a member of Mario Draghi’s coalition government of technocrats, who formerly posed on several occasions dressed in a T-shirt with a Putin portrait, is known to dislike Giorgia Meloni, President of the opposition party Brothers of Italy. The two are now engaged in a lethal fight for the leadership of the Italian right. At the same time, the Polish PiS seems to be reluctant to give up on its present leading role in the European Conservatives and Reformists Group in exchange for a secondary position in a bigger formation. In theory, it seems logical that the two radical, right-wing and conservative groups in the European Parliament, the 67 representatives of the Identity and Democracy Group (ID, where Le Pen’s Party, the German AfD, the Austrian FPÖ and Salvini’s Lega belong) and the 64 representatives of the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR), dominated by the Polish PiS, join forces in one group. By adding to this the 13 currently independent representatives of the Hungarian Fidesz, the new group would be made up of 144 representatives, equal in numbers to the group of Socialists and Democrats, and second to the biggest group of the European People’s Party. (Provided that the only representative of the Hungarian Christian Democratic People’s Party, KDNP, still a member of the group of the European People’s Party, quitted and joined the planned group, the new right-wing formation would supersede even the left-wing group. In other words, the Hungarian Christian Democrats would not only influence the direction of Hungarian, but also that of European politics.)

Leaving behind a big European family of parties apparently leads to political isolation, but a new alliance would certainly earn power and influence in the European Parliament.

Consequently, any country whose political parties are not represented in the big parliamentary groups will inevitably fail to promote their own interests within the co-legislative body of the European Union. This is exactly what has happened after the mid-term election of the European Parliament’s key players: for the first time since 2009 no vice-president has been elected from Hungary. For the past two and a half years Hungary has delegated two vice-presidents; one of them, Klára Dobrev representing the party DK, has stayed away from the recent contest, the other, Lívia Járóka from the party Fidesz (representing the European People’s Party in the preceding election), has entered the ring again as an independent MEP. The result has been embarrassing: from among the 18 candidates for the vice-presidency Ms Járóka has received the lowest number of votes, and therefore she has withdrawn from the second voting round. A similar downturn has taken place in the Parliamentary committees, key actors in the process of legislation. As opposed to the past two and a half years, when Hungarian MEPs had five vice-chair positions in the committees (four MEPs from Fidesz and one from the Socialist party), by now only the Socialist István Ujhelyi retains his post as vice-chair. Lacking support from a big parliamentary group, the politicians of Fidesz have dropped out of the system.

The loss of positions makes it understandable why the Hungarian Prime Minister saves no effort to establish a new family of political parties. In the past nine months the process of creating the ”Pan-European alliance of populist rebels” had at least four major milestones, besides a series of bilateral meetings. Immediately after leaving the European People’s Party, at the beginning of April last year, Orbán had talks with Salvini and Morawiecki in Budapest on possible ways of cooperation. On 2 July, altogether sixteen European political parties signed a declaration on the future of Europe, protesting against initiatives promoting a federalist reform of the European Union, speaking from a common platform of family policy and national sovereignty. Out of the sixteen parties that signed the text last summer only ten parties were represented at the December summit in Warsaw and at the recent Madrid summit. Neither Salvini, nor Meloni were present at the meetings, where some insignificant players did take part, as documented by the family photos taken. These players represented formations such as the Romanian Christian-Democratic National Peasants’ Party, which happened to miss the last two parliamentary elections (and whose only MEP was previously a member of the post-communist PSD), the party of the Polish minority in Lithuania and the Bulgarian National Movement, IMRO, which received a mere 1% of the votes cast in the parliamentary elections last November. On top of that, a few especially dubious characters have also approached the initiative. Although not invited, the Romanian nationalist politician, George Simion was seen sneaking about at the Madrid event. The conference offered the co-president of the party AUR an opportunity to meet and negotiate with the other participants.

As a former football ultra and an active anti-vaccine politician, who organized a rally with some of his simpleminded fellows to desecrate the Austro-Hungarian military cemetery in the valley of Úz, he would also initiate a ban on RMDSZ, the party representing the Hungarian minority in Romania.

Moreover, it was also Simion who previously wanted to outlaw Szeklerland in Transylvania – whereas he regards Viktor Orbán’s political activity as a role model.

While both in Warsaw and in Madrid ten parties were represented, the ID group in the European Parliament has nine members and the ECR group is made up of 18 national formations. It is noteworthy, though, that ODS, the party behind the Prime Minister in the Czech Republic, the Swedish Democrats, currently the third biggest Swedish party, or SaS, member of the coalition government in Slovakia never show up at the meetings. (Each party is a member of the ECR group.) Similarly, the German AfD, regarded by most as a toxic partner, also stays away. By making friends with them Fidesz would risk losing even the remaining links to the German CDU.

In one way or other, the question of Russia is a divisive issue for most of the parties mentioned above.

The Czech government headed by ODS has recently made a decision on supplying ammunition to Ukraine, and the Swedish Democrats have been supportive of a discussion on Ukraine’s NATO membership in the face of the Russian threat.

Yet, the attitude towards Russian politics is a core issue even for those parties that are most willing to form a new alliance. This is well reflected in the burlesque of how the declaration of the Madrid summit has been finalized: the version uploaded onto the PiS website has a specific wording for denouncing „Russia’s military actions”, the version of the Vox party mentions ”external aggression”, while the full version on the National Rally’s website and the short summary published on the English-language blog of the Hungarian Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office write about ”external and internal attacks” threatening the European Union. Information obtained by the Spanish press reflects that the deletion of the text referring to Moscow’s politics was requested by Marine Le Pen, though it may have also been agreeable to the Hungarian Prime Minister, who was about to pay a visit to Vladimir Putin.

The explanation offered by Le Pen to her protest was that she wanted to preserve Emmanuel Macron’s room for manoeuvre in his efforts for deescalating the Ukrainian crisis. A more realistic explanation could be that Le Pen is remarkably understanding with the Kremlin. The French politician repeatedly defended the annexation of Crimea and Russia’s politics in Ukraine. (Although a leading politician of one potential ally, PiS, told Válasz Online that they would by no means cooperate with a party which accepts Vladimir Putin’s efforts to create an empire or fails to recognize Crimea as a part of Ukraine.)

In fact, the great admiration for Russia is not purely ideological: in 2014 Le Pen’s party received a loan of 12 million euros for campaign purposes from a financial institution called First Czech-Russian Bank, a bank with close ties to the superior leaders of the Russian state. (Since then, the bank transferring the loan has gone bankrupt, and the credit has been taken over by an enterprise of former generals of the Russian army.) Just before the French presidential election in 2017 Vladimir Putin had a meeting with the politician, thus showcasing his favoured candidate in the voting process.

Now that getting loans for campaign purposes from a non-EU bank is prohibited by a recent French law, Russia was replaced by Hungary. As reported by the French news radio RTL, Le Pen’s party is about to receive 10.6 million euros from an unidentified Hungarian bank whose name has not been publicly disclosed due to the alleged signature of a clause of confidentiality. Earlier the party’s treasurer was complaining that they applied to each French bank for a loan, but received no response whatsoever.

Insiders of the party have nonetheless denied that Le Pen asked Orbán for funding, either during her visit to Budapest in October, or at the recent meeting in Madrid. Still, it is intriguing that the campaign of a party in another country will be financed from the Hungarian banking sector, probably from a bank co-owned by the Hungarian state, which is otherwise very sensitive to the issue of election meddling. (As it seems highly unlikely that we are dealing with a mere business transaction here and that a Hungarian financial institution would independently deem it a profitable investment to fund Le Pen’s campaign.) Besides funding, the National Rally could see other forms of support as well: Viktor Orbán greeted the participants at Le Pen’s recent campaign event in a recorded video message.

All of this is a move that is not only a slap in the face for Emmanuel Macron, the candidate with the highest rating in the run-up to the presidential election, but also an act of terminating the relationship with a former partner, the centre-right Republicans, the party of ex-president Nicolas Sarkozy. Despite the great camaraderie, though, the French partners still fail to spell the names of Viktor Orbán and Fidesz correctly: among the signatories of the Madrid declaration uploaded onto the National Rally’s website both are misspelt.

Perhaps, by the time the great European right-wing alliance is formed, spelling will be duly managed, too.

Cover photo: leader of French far-right party Rassemblement National (RN) and candidate for the presidential elections Marine Le Pen arrives for a press conference with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in the prime minister’s office, the Carmelita monastery of Buda castle district in Budapest on October 26, 2021 (photo by AFP/Attila Kisbenedek)