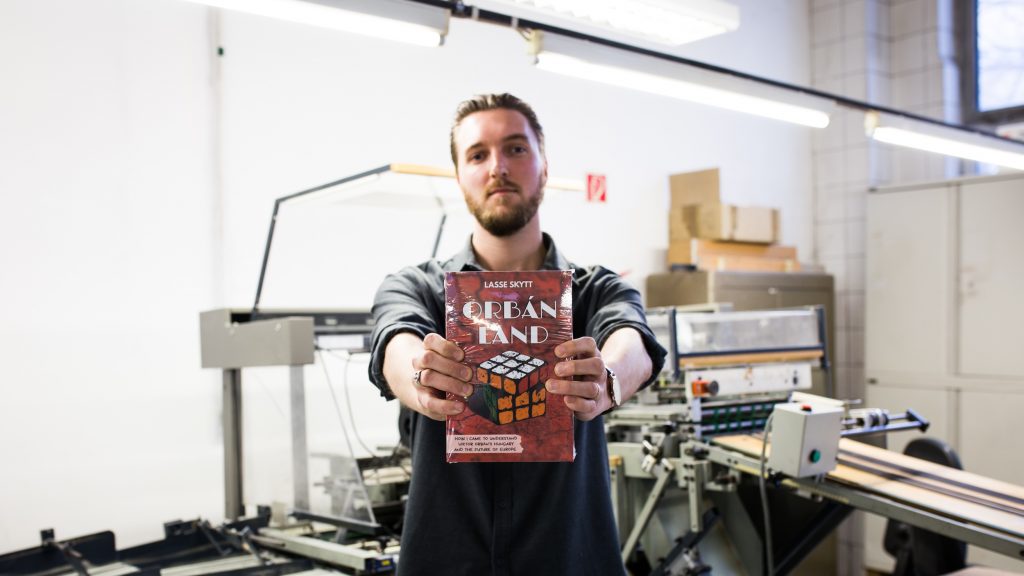

The most divided country in Europe – A young Danish journalist wrote a book about Hungary

Viktor Orbán managed to break certain taboos in Europe but he has not facilitated serious debates in Hungary, according to Lasse Skytt. The young Danish journalist was not pleased with the reports about Hungary so he moved here to see the politics with his own eyes. Válasz Online interviewed him at the very moment the first copies of his new book „Orbánland” have been printed in the press.

– Who is the girl?

– Which girl?

– Well, it sounds good that a Danish journalist comes to Hungary to understand Viktor Orbán’s system then stays for more than five years but…

– …but there is a woman behind everything? Okay you are not mistaken, this goes for my story, too. But it also had to do with pure curiosity. At that point, around 2013, Hungary was becoming very interesting in Copenhagen where I was based. First, the media law caught some attention, then slowly the news about Hungary changed.

– What has changed?

– Prior to that time, when I was reading about Hungary, the focus was always on Jobbik, the then far-right party of the country. Slowly but surely, Orbán became the main protagonist of this story so I was curious to find out what was going on here.

– You had no trust in correspondents?

– Those who live here and have covered the country for more than twenty years became part of the country. Meanwhile they might lose the freshness you need to cover a country. On the other hand,

you cannot understand a country by traveling there for three days, either.

Many foreign correspondents write their articles this way – it is called “parachute journalism” – and it is not the right way. I know that from my own experience. Shortly after I arrived in Hungary, I started to work as a correspondent for Danish newspapers. I was not feeling comfortable. It took a year or even two before I started to think: “Now I understand something.”

– Were you were the typical liberal journalist back then in Copenhagen?

– I was young…

– …You needed the money.

– I needed the money! No. Just kidding. The biggest influence on me – and not only on me – was Francis Fukuyama’s writing about “The End of History”. It was the Bible of everybody in my circles. We all thought that liberal democracy was the final chapter. Besides that, I was always genuinely curious. Also, I was never politically active so I can afford to think freely. I decided to leave all of my usual narratives behind. To come here and work from scratch. It is not easy at all but journalists have the obligation of understanding and describing but not judging a country.

– Why have you changed your mind about Fukuyama?

– The first moment was the attack against the World Trade Center. Then the financial crisis of 2008. And then the migration crisis in 2015.

– In Denmark, you have a popular anti-migrant party. Their leader once called himself anti-muslim. Why was Orbán becoming interesting in Denmark?

– There are similarities between Danmark and Hungary. We had some crises that forced us to discuss important topics: the Muhammad cartoon crisis was definitely one of them. We were forced to have discussions about values, Islam, political correctness, minorities. Even when I was working in Copenhagen for a newspaper, there were several plans of terror attacks against our office. Despite all this, I always stood up for freedom of speech.

– Sweden is more visible from Hungary than Denmark. So we have the impression that Scandinavians do not speak openly about these issues.

– It’s correct that the Swedish attitude is more extreme, often trying to sweep existing problems under the carpet. We, the Danes, do not do this to the same degree. For example, on the issue of migration, many people agree with Hungary. The difference is that half of the voters voted for Fidesz here and the party is possessing full power, while the Danish People’s Party won the last EP elections but it had only 27 percent. Since then, it slipped back to around 20 percent during the 2015 national election and even less in recent months. In Hungary, the politics as a whole is also much more to the right than in Denmark. Our left-wing would be ultra-left in Hungary and Fidesz is ultra-right from the Danish perspective. For example, the leader of the Danish conservatives is homosexual. I can hardly imagine this situation in Hungary.

– What does conservatism mean in Denmark?

– Protecting traditional values, family or church. Though the latter does not mean much to the majority of the people and the Lutheran church is quite liberal. There is only one Danish conservative in the EP group of the European People’s Party – he voted in favour of triggering Article 7 and the exclusion of Fidesz. Yet, while the far-right may not offer the right solution to the problems, it has made them at least a winner of the topic so far.

As a result, change has taken place across Europe: nowadays mainstream parties have recognised that their previous position on migration was unsustainable. The Left, too.

In Denmark, for example, the Social Democrats are cooperating with the Danish People’s Party on the migration policy and they may easily join a coalition. Not surprisingly, however, because they have a lot in common: both parties can count on supporters from the ranks of the working class. In the 1990s, the Left lost its connection with its traditional base all over the world and at some point mostly young intellectuals became their voters. Today’s challenges helped the Left recognise that they should represent the people. Otherwise they will take to the streets as they do in France, in a yellow vest. This left-wing change also required a debate on the migration crisis. And Viktor Orbán has really won that debate on European level. Not on his own but he was the one who managed to sound the alarm.

– If someone puts an important topic on the agenda, is it also okay for you if this politician is lying? About migrant cards, Soros-conspiracy, billboards on every street corner…

– No. It is especially not a great idea to repress the media. The media exists to hold politicians accountable. As soon as the media does not fulfill its task, the politician can lie openly. I visited a pro-government newspaper with a group of Danish students. One of them asked an editor whether she would publish a story with some unpleasant facts about the owner of the newspaper. As a journalist, I would not even think twice about the answer, I would obviously publish the story. However the Hungarian editor hesitated then said she would not. But to me this is not journalism any more.

– Do not tell us that the owner of any newspaper in Denmark is getting unveiled by its own journalist!

– In fact, this happened exactly, twenty years ago. The owner then sold the paper which is in financial trouble ever since but still exists. So does the credibility of its journalists.

– What papers are you working for? Where do they lean to?

– One of them is centre-right, the other is the centre-left so you cannot catch me on this. I work as a freelancer and insist on full freedom and independence. What Orbán is doing is good for many people and many Hungarians are better off than ten years ago. At the same time, I am sensitive to the pressure on freedom, especially the lack of media freedom.

It is difficult to accept that such a price should be paid for either a good migration policy or a more stable economy.

I know that in the past, the mainstream media in Hungary was more biased towards the left but either way it is extremely unhealthy that there are people here who obviously do not report on certain events if it is uncomfortable for the government or their owner – and the two are often the same. What I wish for any country, including Hungary, is to reopen the serious debates. Orbán represents this very strongly on European level which I think is healthy. Here in Hungary however, he has not done the same. It is not only reflected in the media sector but also in the occupation of state institutions which, by definition, should not be politicised. The Hungarian electoral system was tailored to the competition of two large parties but there are no two large parties, only one and a lot of smaller ones. It is also very unhealthy for the Hungarian democracy.

– Let’s not drop the hot potato: did you wrote a pro- or anti-Orbán book?

– Neither. This is the most important part of it. I do not repeat the Mafia State Theory, I do not mention the great corruption issues but I did not use the scripts of the authors celebrating Orbán either. I try to raise the discussion one level up by looking at migration, nationalism, human rights, family values, among other things. It is plain to see that the disagreements on these issues have lead to the division of Europe and Hungary today. I also look at moral, cultural and social psychological causes: These are important factors when one calls himself conservative or liberal. What I strongly oppose is that there should be no open or sober debate between the representatives of the different attitudes. I know it sounds like some old hippie dream but it is extremely important to have a meaningful discourse.

Is it a coincidence that Trump, Brexit, the Yellow Vests, Orbán and more are all happening within a few years? I do not think so.

The liberal consensus has collapsed and real politics is alive once again, moving and boiling. Anyone who does not see this and does not try to understand the other part will be handicapped.

– Maybe it is the illiberal consensus that is coming. Singapore and China show that the economy can be successful without democratic values.

– It could be an economic success. So could a dictatorship or an absolute monarchy. But then can we forget about democracy. Democracy is when the voice of the people counts. Democracy means that at least we can change something with our vote. Well, to be honest, I do not vote. As a journalist, I do not want to be committed to any political side at all. I am not saying that everyone should do this in our profession, I know that journalists also have private life, they have families so they can have political interests as any other citizen…

– Do you have a family?

– I have a wife. The woman you have already asked about.

– Is she Hungarian?

– She is from Iceland. She is at medical school in Debrecen, studying to become a doctor.

– Are you planning to stay in Hungary?

– I do not know but I think partly yes. Hungary is a great terrain for me.

– So what is new in your book about Orbán? Something people abroad were unaware of?

– From the outside, Hungary seems to be united. It looks like everybody have lined up behind Viktor Orbán. This mental image is sometimes vivid in Hungarians’ minds as well. In reality, however, Hungary is the most divided country in Europe. Half of the citizens have voted against Orbán, the other half for him. The gap between the two sides is much wider than anywhere else.

This is not me saying that but findings from scientific research. Of course, it is a question how Jobbik could be classified. I also try to answer this in the book. There is an interview with one of Jobbik’s leaders, Márton Gyöngyösi, but also with Mária Schmidt, the Fidesz-allied historian and the late Andy Vajna. So is the former socialist PM, Ferenc Gyurcsány. There are a total of sixteen interviews – these make up one third of the book. Orbán, of course, dominates Hungary so the title of the book is “Orbánland”. The fact that Hungarians are divided was already visible by how the title was received – even before the book was published. Leftists do not like it because they think the title raises Orbán too high, while Fidesz-fans immediately saw an attack: “The liberal foreigner is getting on the prime minister again.” None of these is true. The book’s title is neither an attack nor a celebration.

– Which interviewee was the most exciting?

– Tibor from Veszprém.

– Tibor Navracsics? The Fidesz-member EU commissioner, a native of Veszprém?

– No, no! Just Tibor. He is neither a politician, nor a famous man. Just a Hungarian man from Veszprém. His views were the most thoughtful.

– What did he say?

– It is in the book. Read it!

Photo: Szabolcs Vörös / Válasz Online